DISCLAIMER: The article contains mixed authorial voices and fabricated information for performative effect. For broader context, make sure to read “Infinite Meaning“, as a guide for reading avant-garde fever notes.

Alright, so welcome back to the lectures on interdisciplinary semiotics and the Applied Sciences. Last time, we ventured into the intricate realm of Saussurean linguistics, specifically examining the signifier-signified theory. Ferdinand de Saussure posited that the ‘signifier’ refers to the conceptual or phonetic element of language, while the ‘signified’ pertains to the tangible object or concept in the physical world. 🤔💭

We concluded, however, that this framework was not particularly beneficial for our purposes. It remains overly dualistic and ensnared in the Cartesian dichotomy—a philosophical perspective we have decidedly repudiated. We must not allow ourselves to be mired in such limiting constructs.

Following this, we explored the theory of double segmentation, which proceeds into the analysis from the vantage point of the Lacanian subject. This concept, drawn from Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic theory, pertains to the ‘subject of the pure signifier‘—an entity whose existence is constituted through language and symbolic structures.

Derrida: Deconstruction etc.

Today, we plunge into the depths of Derridean thought. Jacques Derrida, a luminary in French philosophy, is renowned for developing deconstruction—a form of semiotic analysis that dissects and subverts traditional structures of meaning. We shall scrutinize the myriad approaches Derrida employs to tackle the pervasive cultural issues we touched upon in our previous session.

But before we proceed, I must express my gratitude to my wife 💃 for her invaluable input 🤯💥🤣. She was present at our last lecture—perhaps you noticed a distinguished woman 👩🙅♀️ in the audience, one who stands apart in age from the rest of you. That was indeed my wife, who is also a faculty member here, specializing in feminist post-structural theory within the humanities department 📕🗑️🤣. Her insights continually enrich our discourse, and for that, I am deeply grateful. 😁😂🍭

Jokes aside, my wife is drawing from the various strengths of literary critique, which are essentially an outgrowth of Derridean analysis. Derrida’s method of addressing issues is grounded in the concept of polarity, giving rise to our double segmentary approach. When examining the psychotic and the tyrannical, we must recognize that every system, from a Marxist perspective, inherently contains a bourgeois element. Thus, no state is devoid of a certain tyrannical aspect.

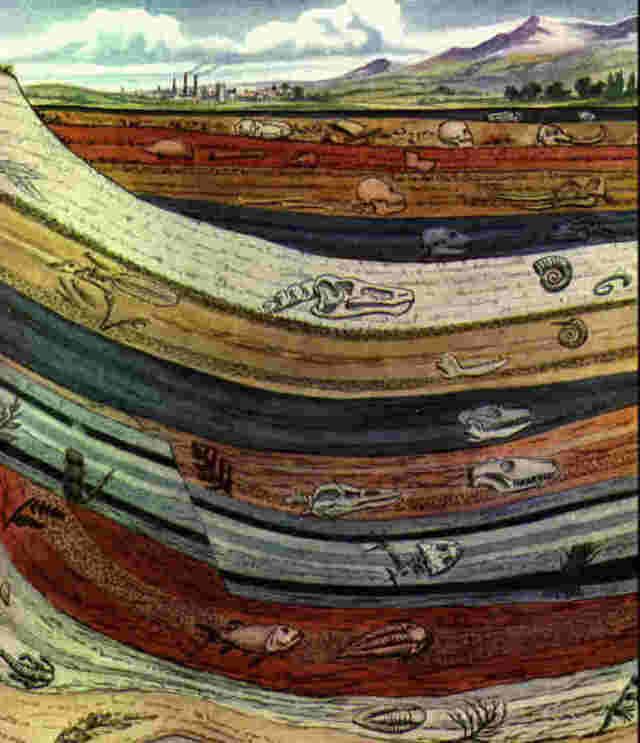

This insight extends even to our own university. You might think it’s a bastion of academic freedom, yet Hegel, with his lofty ideals for the university, faced significant criticism, particularly from French intellectuals. Figures like Derrida emerge to destabilize these entrenched, stratified structures. Imagine a geological formation, with its layers of sediment; Derrida’s work is akin to wielding a pickaxe against these layers, exposing and interrogating the sedimentation of meaning and power.

Linguistic Analysis: Derrida & Freud

Derrida’s literary critique proceeds into the subtext of texts, akin to a form of Freudian analysis applied to language and literature. This approach symbolizes the intersection of two potent theoretical currents: the linguistic turn in philosophy and the burgeoning field of depth psychological analysis. The latter began with Freud and evolved through French post-Freudian and feminist scholars.

Derrida’s deconstruction method invites us to look beyond the surface, to uncover the hidden assumptions and contradictions within texts and systems. This approach destabilizes the apparent coherence and reveals the inherent instability of meaning, much like how Freud’s psychoanalysis sought to unearth the unconscious drives and conflicts beneath human behavior.

The confluence of these theoretical streams created an explosive intellectual milieu. The linguistic turn, emphasizing the centrality of language in shaping human experience, intersected with the deep psychological insights of Freudian analysis, yielding a rich terrain for critique and exploration. In this context, Derrida’s work challenges us to rethink the foundations of our cultural and intellectual structures, exposing the intricate interplay of power, language, and meaning.

And then there was also the Lacanian idea of the objet petit a, a concept introduced by Jacques Lacan referring to the unattainable object of desire, a core element in his psychoanalytic theory.

Derrida’s approach to texts is deeply psychoanalytic. He not only dissects the text itself but also scrutinizes the author. Recall the term “death of the author”, a notion popularized by Roland Barthes. This concept argues that once a text is produced, the author’s intentions and biographical context should no longer dictate its meaning. The text, emerging from the author’s unconscious, enters the public domain, where its ideas disseminate and fragment.

In our previous lecture, I hope it became evident that this notion is fundamentally flawed. There are no isolated incidents in the realm of textual and intellectual production. Derrida underscores the interconnectedness of texts and ideas, emphasizing that meaning is not fixed but perpetually subject to reinterpretation. This dynamic nature of meaning challenges any attempt to anchor a text to a singular, authoritative interpretation.

Derrida’s deconstruction reveals that texts are part of a broader web of signification, where every interpretation is influenced by other texts, contexts, and the readers’ own perspectives. The idea of the “death of the author” liberates texts from authorial intent, allowing them to live multiple lives through diverse readings. Yet, this freedom also underscores the inherent instability and multiplicity of meaning, which Derrida skillfully navigates.

By analyzing texts through this lens, Derrida aligns with the Lacanian notion of desire and the elusive objet petit a, suggesting that meaning itself is an unattainable object, always deferred, never fully grasped. His critique extends beyond the text to the structures of power and knowledge that shape our understanding, continually destabilizing and reconstructing the intellectual landscapes we inhabit.

Objet a: Generic MacGuffins

To make this more concrete, consider the concept of the objet petit a as akin to the MacGuffin in film and literature. A MacGuffin is an object or goal that drives the plot forward but whose specific nature is ultimately irrelevant to the story. It is a catalyst for action, much like how the objet petit a represents an unfulfilled desire that motivates individuals but remains perpetually out of reach. For example, in Alfred Hitchcock’s films, the MacGuffin could be anything from stolen documents to a piece of jewelry; its exact identity doesn’t matter—what matters is the characters’ pursuit of it, which propels the narrative.

In a similar fashion, Derrida’s deconstruction reveals how our pursuit of stable meaning is akin to chasing a MacGuffin. The quest itself exposes the underlying power structures and biases that shape our interpretations and understanding. For instance, in a political speech, the master signifier might be “freedom.” While the exact nature of “freedom” can be endlessly debated and is context-dependent, the pursuit of this ideal reveals the speaker’s underlying values and ideological commitments.

By applying these ideas, we can see how Derrida’s methods enable us to uncover the hidden dynamics within any text or discourse. This approach doesn’t just remain an abstract exercise but becomes a practical tool for critically engaging with the complex and often contradictory messages we encounter in everyday life.

Derrida: The Geology of Text

So today, we’ll proceed deeper into Derrida’s approach and explore how it can help us better understand not only texts but also the broader cultural context in which they exist. We’ll examine some key concepts from his work, such as “différance” and “deconstruction”, and discuss how these can be applied to various fields within the Applied Sciences.

By the end of this lecture, I hope you will have gained a greater appreciation for the complexity and richness of Derrida’s thought and its relevance to interdisciplinary semiotics.

Imagine Derrida’s framework as a geological formation, where each stratum of text and meaning is inextricably linked with others. To analyze one layer without considering the others would be incomplete. This interconnectivity repudiates a simplistic relativism, which Derrida himself firmly rejected. He explicitly stated, “There is not a shred of relativism in my own writing”. His focus is not on psychologizing the subject but on examining the cycle of signification that flows through the subject as they express themselves through words, which originate from the public domain.

Words, although publicly accessible, are crafted in particular, constrained ways that produce a multitude of interpretations. These interpretations then feed back into the interpretive community, creating a dynamic and ever-evolving discourse.

Words, although publicly accessible, are crafted in particular, constrained ways that produce a multitude of interpretations. These interpretations then feed back into the interpretive community, creating a dynamic and ever-evolving discourse.

Consider how layers of sediment accumulate over time, each layer representing different periods and conditions. Similarly, texts and discourses are composed of layers of meaning that build upon each other. Derrida’s concept of deconstruction can be likened to the process of geological excavation. By digging through these layers, we can uncover the historical and cultural contexts that shape a text’s meaning.

Derrida’s analysis also resonates with Gilles Deleuze’s idea of territorialization. In geology, territorialization refers to the formation of stable landforms from dynamic processes like sedimentation. In a cultural context, territorialization involves the stabilization of meanings and identities within a text or discourse. Just as geological formations are subject to forces that can transform them, meanings within a text are always subject to reinterpretation and change.

For instance, imagine a sedimentary rock composed of distinct layers. Each layer contains fossils, minerals, and other materials that tell a story about the earth’s past. Similarly, a text contains layers of meanings, references, and contexts. Deconstruction involves analyzing these layers to reveal the underlying assumptions and power structures.

Moreover, Deleuze’s concept of deterritorialization aligns with Derrida’s idea of deconstruction. Deterritorialization in geology refers to the erosion and reformation of stable landforms, akin to the way deconstruction disrupts fixed meanings and opens up new interpretive possibilities. Just as the earth’s surface is constantly reshaped by natural forces, the meanings within a text are continually reinterpreted by readers and critics.

For example, in literature, a classic text like Shakespeare’s Hamlet can be deconstructed to reveal different layers of meaning: historical context, authorial intent, psychological motivations, and contemporary relevance. Each reading adds a new layer to the sedimentary formation of the text’s interpretation.

The Trace: Instability of Historicity

Now, let’s explore “différance”, a term Derrida coined to capture the dual processes of deferral and differentiation that occur in language. Unlike a fixed meaning, “différance” suggests that meaning is always deferred, never fully present, and constantly differentiated by the context and interplay of signs. This perpetual deferral creates an endless chain of signification, challenging the notion of a stable, singular meaning.

Deconstruction, Derrida’s method of analyzing texts, involves uncovering the inherent instability and contradictions within them. By deconstructing a text, we reveal the hidden assumptions and binary oppositions that structure it. This process destabilizes traditional hierarchies and opens up new possibilities for interpretation.

Plato’s Pharmakon

Derrida’s deconstruction of Plato’s Phaedrus focuses on the concept of the pharmakon, a term that Plato uses to denote both remedy and poison. By examining this dual meaning, Derrida argues that the text itself subverts the binary opposition between good and evil. The pharmakon destabilizes the idea that language can offer a clear, unambiguous sign. The presence of such a term in Plato’s work reveals that meaning is inherently unstable and context-dependent. This deconstruction exposes the inherent contradictions in the text, suggesting that attempts to fix meaning are ultimately futile because every signifier carries within it the potential for multiple, often conflicting, interpretations. Thus, Derrida shows that even the foundational texts of Western philosophy are built upon unstable grounds, challenging the very possibility of achieving definitive knowledge through language.

Premise 1: The term pharmakon in Plato’s Phaedrus can mean both “remedy” ❤️🩹 and “poison.” ☠️

- Example: In medical contexts, a drug can be both healing and harmful depending on dosage and use.

Premise 2: The dual meaning of pharmakon destabilizes the binary opposition between good 👼 and evil 😈.

- Example: Antibiotics cure infections (good) but can also cause antibiotic resistance (evil).

Premise 3: Language aims to provide clear and unambiguous signs to convey meaning.

- Example: Legal language strives for precision to avoid misunderstandings but still often leads to different interpretations in court cases.

Premise 4: The presence of a term like pharmakon in philosophical texts demonstrates that meaning is inherently unstable and context-dependent.

- Example: The word “freedom” can signify personal liberty in one context and economic deregulation in another, showing its context-dependent meaning.

Conclusion: Therefore, the attempt to fix meaning through language is ultimately futile, as every signifier carries within it the potential for multiple, often conflicting, interpretations. Derrida’s deconstruction of pharmakon reveals the unstable grounds upon which Western philosophy is built.

Saussurean Linguistics

Derrida critiques Ferdinand de Saussure’s structuralist distinction between the signifier (the word) and the signified (the concept it represents). Saussure posits a stable relationship between the two, but Derrida introduces the concept of “différance” to demonstrate that this relationship is not stable but perpetually deferred. Différance involves both deferral and differentiation, indicating that meaning is always postponed and constructed through a play of differences within language. This undermines Saussure’s claim of a stable linguistic structure, revealing instead a fluid, dynamic system where meaning is never fully present but always in a state of becoming. Derrida’s argument challenges the structuralist assumption of fixed meanings and highlights the continuous and context-dependent process of meaning-making, thereby reshaping our understanding of language and communication.

Premise 1: Saussure posits a stable relationship between the signifier (the word) and the signified (the concept it represents).

- Example: The word “tree” is thought to consistently represent the concept of a tree.

Premise 2: Derrida introduces the concept of différance, which involves both deferral and differentiation. 🥴😵😖👌

- Example: The meaning of “tree” can vary depending on whether it is a Christmas tree, a family tree, or a data structure in computer science.

Premise 3: Différance suggests that meaning is always postponed and constructed through a play of differences within language.

- Example: The word “bank” can mean a financial institution or the side of a river; its meaning depends on the surrounding words (context) that defer its specific meaning.

Premise 4: The relationship between signifier and signified is thus not stable but perpetually deferred.

- Example: In literature, the meaning of the word “rose” can differ vastly from its botanical definition when used symbolically, e.g., “a rose by any other name.”

Conclusion: Therefore, the structuralist assumption of fixed meanings is undermined, revealing a fluid, dynamic system where meaning is never fully present but always in a state of becoming.

The Concept of Presence

Western metaphysics traditionally emphasizes the idea of presence as the foundation of meaning and truth. 🤔💭

Derrida deconstructs this notion by showing that presence is always constructed through the exclusion of absence. In works like Of Grammatology, he argues that what we consider as ‘presence’ is actually dependent on what is not present—an absent other that haunts every act of signification. This interdependence of presence and absence means that any claim to absolute presence is inherently flawed. By revealing the constructed nature of presence, Derrida destabilizes the metaphysical certainties that underpin much of Western thought, suggesting that our understanding of being and meaning is always contingent, never complete. This deconstruction forces a reconsideration of how knowledge and truth are constituted, emphasizing the provisional and constructed nature of our conceptual frameworks.

Premise 1: Western metaphysics emphasizes presence as the foundation of meaning and truth.

- Example: Philosophical and religious texts often stress the importance of the present moment or divine presence.

Premise 2: Derrida argues that presence is constructed through the exclusion of absence.

- Example: The concept of “light” is understood in contrast to “darkness,” which it excludes but depends on for its definition.

Premise 3: Presence depends on the absent other that haunts every act of signification.

- Example: A photograph of a loved one signifies their presence but also poignantly highlights their absence.

Premise 4: Any claim to absolute presence is inherently flawed because it relies on the interdependence of presence and absence.

- Example: In the phrase “I am here,” the concept of “here” only makes sense in relation to “there,” the absent space.

Conclusion: Therefore, the metaphysical certainties underpinning Western thought are destabilized, suggesting that our understanding of being and meaning is always contingent and never complete.

Rousseau’s Confessions

Derrida’s deconstruction of Rousseau’s Confessions reveals the contradictions and gaps within Rousseau’s attempt to present a coherent and truthful self-portrait. Rousseau’s narrative strives for authenticity and self-consistency, but Derrida shows that the act of writing itself introduces fragmentation and mediation. Language, being a system of signs, cannot perfectly capture the essence of the self; it always involves a degree of interpretation and re-interpretation. This means that Rousseau’s self-portrait is necessarily incomplete and internally conflicted. Derrida’s deconstruction exposes these conflicts, demonstrating that the search for a unified self through language is illusory. By doing so, Derrida highlights the limitations of autobiographical narratives and the broader implications for understanding identity and selfhood as constructed and fragmented rather than natural and cohesive.

Premise 1: Rousseau’s Confessions aims to present a coherent and truthful self-portrait.

- Example: Autobiographies generally strive to present an accurate account of an individual’s life.

Premise 2: The act of writing introduces fragmentation and mediation.

- Example: Writing about personal experiences can never fully capture the raw emotions and context of the events.

Premise 3: Language, as a system of signs, cannot perfectly capture the essence of the self.

- Example: Describing a complex emotion like love or grief can never fully convey the personal, internal experience.

Premise 4: Rousseau’s self-portrait is necessarily incomplete and internally conflicted due to the limitations of language.

- Example: Rousseau’s narrative might omit or alter details unconsciously, revealing the subjective nature of memory and self-representation.

Conclusion: Therefore, Derrida’s deconstruction exposes the conflicts within Rousseau’s narrative, demonstrating that the search for a unified self through language is illusory and highlighting the limitations of autobiographical narratives in understanding identity.

Multiplicity of Interpretation; Not-Relativisim

And Derrida famously asserts that every person becomes the pretext to the text they are reading, as they inevitably bring their own paradigmatic framework to their interpretation. However, we must not mistake this for a “free-for-all” relativism. Instead, it acknowledges the multiplicity of interpretations while maintaining that each interpretation carries a confessional aspect. In any text, according to Lacan, we encounter the master signifier—the central, high-value concept around which meaning revolves.

For instance, my wife pointed out to me in private that I seemed distinctly anti-technology. This observation reveals that my master signifier might be against technology. It’s something we argue about frequently, especially when she’s engrossed in her devices while I long for simpler, more direct interactions like we used to have during dinner. The contemporary landscape, dominated by online communication tools, often feels like a wasteland of misplaced time and energy.

People, as you might know, often appear quite unintelligent in their communications, and this is exacerbated on the internet. 🤦♀️

This pervasive foolishness is a daily observation for me, making online interactions even more exasperating.

Consequently, I have stopped reading my emails and generally avoid online posts. This aversion might stem from an anxiety disorder.

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaAAAAAAAAAAAAAA 😭

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaAAAAAAAAAAAAAA 🥹

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaAAAAAAAAAAAAAA 😖

I once sought therapy, but it was unproductive 😭 because the therapist lacked understanding of linguistic theory and the fundamental principles of the positivist tradition. 😔👌

At that time, I was deeply influenced by Bertrand Russell 🤣🤷♀️, who championed logical positivism 😂🤦♀️—a stark contrast to the therapist’s approach.

Returning to our primary discussion, Derrida’s insistence on the master signifier is crucial. It underscores that while interpretations are varied, they are not arbitrary. Each interpretation reveals the interpreter’s own central concerns and biases. In my case, my apprehension towards technology colors my readings and interactions. This is a manifestation of the master signifier at work—shaping and directing the myriad ways in which we engage with texts and, by extension, with the world around us.

This nuanced understanding of Derrida’s approach invites us to reflect on our own master signifiers. It challenges us to consider how our personal paradigms influence our interpretations and interactions. It’s a reminder that while our readings are subjective, they are anchored in deeply ingrained, often unconscious, value systems. This is the essence of deconstruction: to reveal these underlying structures and interrogate their impact on our understanding of texts and cultural contexts.

The Master-Signifier: Undue Valorization

“As a regular visitor to this site, do you find this structure beautiful?”

“Of course not! This is the only place in the city where I can look out and avoid seeing this hideous thing.”

Derrida, of course, pierces through the tradition of our pre-established values. Take, for instance, my aversion to technology and my insistence on the importance of being present. Derrida would critique this very stance, arguing that the notion of presence is an illusion. He posits that at the core of being, there is only a void that cannot be fully captured by linguistic approximations. Our language, with all its limitations, merely reflects our own confessional biases and experiences, forming polarities rather than absolute truths.

In a similar vein, both Derrida and my wife often seem to think I am a bit of an idiot. I’m not afraid to admit that I sometimes am. In the last lecture, for instance, I got quite emotional and ended up in hot water with some students afterward.

But I think we managed to talk it out. I was getting too personal, resorting to ad hominem attacks, and I regret that. So, let’s move on with today’s lecture.

Derrida’s framework revolves around the interplay of polarities, integrating psychoanalytic approaches into literary theory in response to linguistic philosophy. Yet, Derrida’s work has not been without criticism. Some of my wife’s colleagues—intellectuals you might be familiar with (I see some of you chuckling; you know who I’m talking about)—have pointed to a paper titled “The Two Strata of Feminist Discourse”. This paper critiques Derrida’s early work for being masculinist, despite his rejection of relativism. It argues that his focus on destabilization often undermines the stability provided by the mother-child synthesis, a fundamental aspect of cultural formation.

Derrida’s relentless pursuit of deconstruction seeks to uncover the negative spaces within structures of meaning, which some interpret as a masculine-centric approach. My wife often tells me, “You don’t understand technology”, which might be true, but I also see myself as providing a form of stability.

Let’s unpack this a bit more. Derrida challenges the idea of a fixed center or stable meaning. He suggests that every supposed center is an arbitrary construct that marginalizes other possible interpretations. This destabilization process mirrors psychoanalytic practices, revealing the underlying structures of our thoughts and cultural narratives.

Wait, the Construction Site Outside is Bothering ALL OF US

Ok, I hope we can settle down now. The noise from the construction site outside is quite disruptive. 😭

It actually serves as a perfect metaphor for the issues inherent in our relationship with technology. I know some of you might be chuckling, thinking, “Here he goes again, the old guy railing against technology. He doesn’t get Snapchat, Twitter, or Facebook”. But this is a significant concern, and the Derrideans among you might point out how polarized and polarizing my views 👁️ can be. 💃

[The lecturer shuffles his notes] Let’s get back on track. Derrida’s literary theory has had deep impacts on society. To summarize briefly, during the ⚠️ Science Wars ⚠️, many critics accused Derrida of promoting dangerous relativism. They argued that his deconstruction threatened the foundations of scientific inquiry. However, Derrida firmly rejected the label of relativist, asserting that his work was not intended to undermine science but to explore the complexities of meaning and interpretation.

With the rise of technology, we have witnessed a troubling trend toward intellectual shallowness 🤕. Our cultural focus has shifted from deep, critical engagement to superficial obsessions with reality TV stars and consumerism. This shift has rendered much of our intellectual tradition seemingly irrelevant. 🥹🥲😭 Marx’s critiques of capitalism, for example, are often ignored in favor of more trivial pursuits. 🙅♀️💥

And now, I realize I’m veering off track. Let’s refocus. Derrida’s later work took on an ethical dimension, particularly in his exploration of the concept of the “face of the other” 🫠, which draws on Emmanuel Levinas’s philosophy. This idea emphasizes the ethical responsibility we have toward others, recognizing their intrinsic value and humanity. Derrida also engaged with animal rights, highlighting the ethical implications of how we treat non-human animals.

[The lecturer shuffles his notes more rapidly] I apologize for having to rush through my notes. I have an appointment afterward, so I need to move quickly. 🏃♂️💨👟

Summary

In essence, Derrida’s work challenges us to reconsider our preconceptions and biases, whether about technology, ethics, or our cultural values. His deconstruction method encourages us to look beyond surface meanings and to understand the deeper, often hidden structures that shape our world. This critical perspective is invaluable in today’s fast-paced, technologically driven society, urging us to maintain a nuanced and thoughtful approach to the complexities of contemporary life.

So, as we continue our exploration of Derrida, let’s keep these ideas in mind. The critical tools he provides can help us navigate the often overwhelming flood of information and cultural noise, enabling us to find deeper meaning and ethical clarity in our engagements with the world.

[The lecturer flips through his notes]

So, if there is one thing I want you to take away from these lectures, it’s the importance of analyzing a person’s discourse by examining the underlying polarities. Identify their master signifier—their pivotal concept that shapes their worldview. This method reveals the core of their ideological framework.

Additionally, approach this analysis from an ethical perspective. Recognize all beings as beings with intrinsic value. This perspective is not about relativism but about acknowledging the inherent worth of each individual and their experiences.

So, here’s your task: Find a text and perform a Derridean deconstruction. I want you to dissect the text, uncovering the hidden assumptions and contradictions. Engage in this process with a sense of play, akin to Derrida’s concept of “play” in semiosis. This approach should not be limited to theoretical exercises but applied in your daily life as well.

We’ll proceed deeper into these ideas in our upcoming lectures. Take care and see you next time. 🫡👌

Leave a comment